Spine Sign

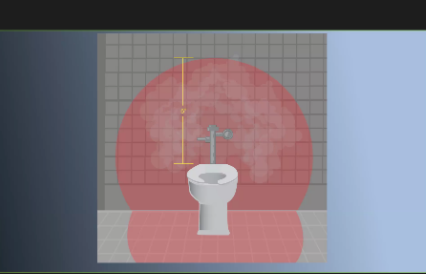

/A 50 YEAR OLD PATIENT WITH ALCOHOL ABUSE PRESENTS WITH SEVERE EPIGASTRIC ABDOMINAL PAIN AND DYSPNEA. YOU OBTAIN THE BEDSIDE US CAPTURED ABOVE. WHAT SINGLE LABORATORY TEST WILL HELP CONSOLIDATE THIS PATIENT'S PRESENTATION?

Spine Sign

We had a fantastic faculty session with Dr. Jessica Baez on Point of Care Ultrasound for the lungs. Check that out here if you missed it! We’re continuing on the POCUS train with review of “spine sign” in pleural effusion.

Positive Spine Sign is a clear view of several thoracic vertebrae through the effusion. If you look closely at the ultrasound above, you can see the outline of several vertebra. It is 92% sensitive and ~93% specific for presence of a pleural effusion.

Negative Spine Sign: Let’s compare with normal lung showing a negative Spine sign. In normal lung, the air within the lungs should obstruct your view of the thoracic vertebra.

In the patient in our case with alcohol abuse presenting with severe epigastric abdominal pain and dyspnea. His bedside US demonstrates a pleural effusion. In the context of alcohol abuse with epigastric pain, my differential includes gastritis, PUD, pancreatitis, Mallory-Weiss Tea, Boerhaave, acute hepatitis; less likely: ACS, pulmonary embolism, aortic ulcer/dissection. With the evidence of pleural effusion based on spine sign, I begin thinking about how any of these differential diagnoses can lead to an effusion. My differential narrows to esophageal perforation (if clinical history of significant retching) versus acute pancreatitis with pleural effusion. A single laboratory test performed on pleural fluid that could consolidate the abdominal pain and the effusion would be a pleural fluid amylase level. Pleural fluid amylase >ULN for serum amylase, or a pleural fluid : serum amylase ratio > 1.0, is indicative of pancreatitis or esophageal rupture. In the case above, the patient has an pancreatic pleural effusion with ascites.

Further references: Extension of Thoracic Spine Sign

~Natalie Hood, MD