The Art of Interpreting EBM: What is The Data on Heparin in ACS?

/We’ve had our AHD on ACS and we know that starting anticoagulation in acute coronary syndrome is a Class I recommendation, but when you dive into the guidelines you find this interesting gem:

“Studies supporting the addition of a parenteral anticoagulant to aspirin in patients with NSTE-ACS were performed primarily on patients with a diagnosis of “unstable angina” in the era before DAPT and early catheterization and revascularization. In general, those studies found a strong trend for reduction in composite adverse events with the addition of parenteral UFH to aspirin therapy.”

- 2014 ACC/AHA Guidelines for Management of NSTEMI-ACS

Going through the literature on heparin in ACS is an interesting historical adventure. Today, we all train with high sensitivity troponins, 24-hour cath labs, DAPT… but there was a time when the treatment for ACS involved bed rest for 48 hours followed by sitting up at bed with progressive return to activity over 2 weeks.

How did the treatment of ACS evolve from that to what it is today and how does heparin fit into it?

First let’s start with the pathophysiology of Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS) as compared to Coronary Artery Disease (CAD). The latter is the chronic progressive narrowing of the coronary artery lumen due to years of Burger King and smoking, leading to supply-demand mismatch and angina. ACS develops when that plaque ruptures, exposing the blood to pro-coagulant factors resulting in thrombus formation and acute narrowing of the diameter of the artery. Given this pathophysiology, it makes sense to give them medications to stop the coagulation cascade with anti-platelets and anti-coagulants.

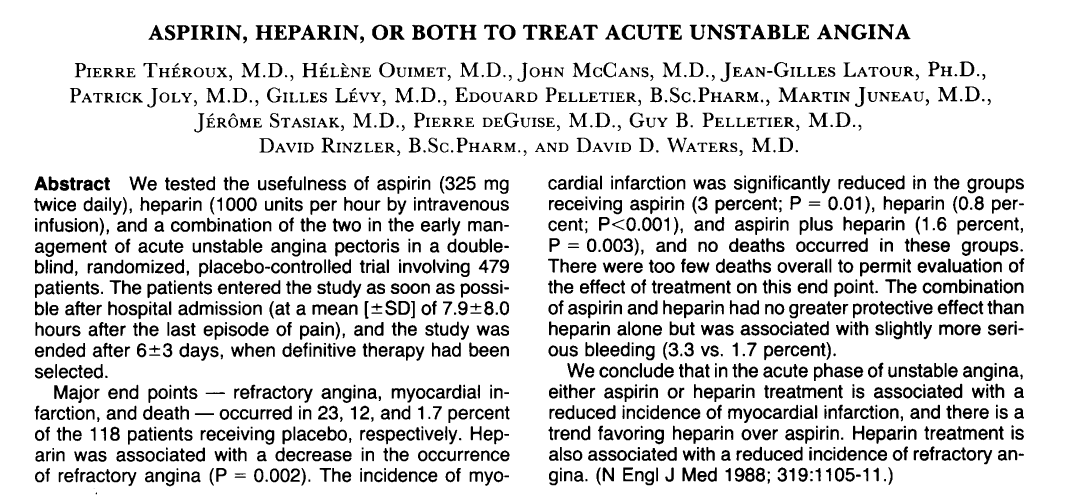

The first RCT was by Theroux et. al in 1988 which looked at nearly 500 patients with symptoms of unstable angina and EKG changes. They were randomized to placebo* vs ASA (325mg BID) vs heparin gtt with daily aPTT vs ASA and heparin gtt for 3-9 days. They found that all interventions were better than no intervention when evaluating primary ends points of 1) refractory angina, 2) MI, and 3) death. However, the study was underpowered to identify any significant differences between the intervention arms. So, we can probably say that heparin has some sort of therapeutic effect in ACS.

*This means that they admitted patients with UNSTABLE ANGINA and gave them infusions of saline and sugar pills!! That’d be hard to get through an IRB today…

Since it appears that heparin helps in ACS, Cohen et. al (1994) evaluated what the long term effects of anticoagulation were. In this RCT, they compared ASA vs ASA + anticoagulation with the primary end points being 1) refractory angina 2) MI and 3) death, evaluated at 2 and 12 weeks. Patients in the anticoagulation arm were started on heparin and transitioned to warfarin at days 3 or 4 to be continued until the end of the study. They found a significant decrease in primary-end-point-events at 14 days (p=0.004) in the anticoagulated group!

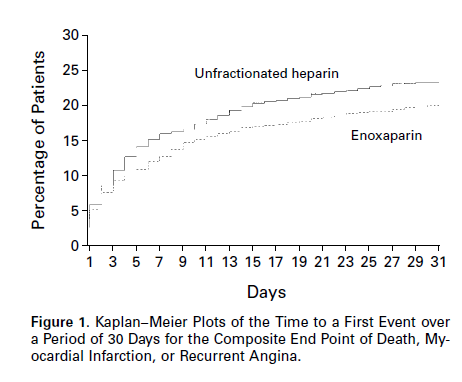

So they continued researching anticoagulation. In Cohen et. al (1997, ESSENCE), they looked at anticoagulating with Lovenox as compared to heparin because heparin is hard to use; up to 50% of patients on infusions are not therapeutic at 24 hours. This study was a multicenter RCT that looked at over 3000 patients, randomizing them to ASA + heparin gtt vs ASA + Lovenox comparing the end points 1) refractory angina 2) MI and 3) death at 48-hours, 14-days, and 30-days. There were no significant differences at 48-hours but at both 14-days and 30-days, Lovenox had decreased rates of MIs and refractory angina, but there was no significant decrease or trend in mortality.

Of the original heparin studies, the closest to what we do today was Holdright et. al. (1994) which looked at in-hospital prognosis with 48-hours of heparin gtt + ASA vs ASA. This is a fascinating study that will grate your guideline-drive-brain. They enrolled patients with unstable angina and monitored their ST-segments over 48 hours. Transient Myocardial Ischemia (TMI) was defined as chest pain with EKG changes while on maximal medical therapy. They found no changes in TMI between the study arms. In the discussion they mention one particular patient who had a total 1,360 minutes of ST-changes with chest pain which they… recorded… oh how times have changed. Heparin in addition to ASA did not confer any mortality benefit at 48-hours.

Finally, SYNERGY (2004) evaluated Lovenox vs heparin in ACS in the setting of early invasive strategy. In this study, nearly 10,000 patients were randomized to heparin + ASA vs Lovenox + ASA in patients undergoing LHC (mean time 22-hours). There was no difference in mortality at 14 or 30 days.

You’ll notice that a lot of these studies evaluated the effects of anticoagulation over a much longer time period than we expect it to work. Doing this they found an interesting rebound effect - when you stop heparin, the rates of angina and MI increase! Theroux et. al (1992) looked at this and the rates of MI increased nearly 3-fold, but are somewhat tempered by aspirin use.

Additionally, the age of this data makes it hard to interpret. The heparin protocols were different than today’s, the ASA dosages were different, and most importantly the risk stratification we do today was nonexistent. For instance, in the ESSENCE trial (Lovenox decreased mortality at 14 and 30d in ACS), there was no reporting of biomarkers for the patient groups. Is it possible that the heparin group had significantly more troponin leaks - i.e more NSTEMI vs unstable angina? Does that make a difference? We do not know. Additionally, in the age of plavix, aspirin and early intervention for most of the patients studied, does heparin play a significant role anymore, or is it just vestigial? Who knows…

Let’s summarize what we’ve learned (tl:dnr)

Heparin makes physiologic sense in ACS

Theroux et. al. 1988 showed that heparin + ASA and heparin are both better than sugar water, so anticoagulation does something.

Cohen et. al (1994) and ESSENCE both showed long term benefit from anticoagulation at 14 and 30 days, but not at 48-hours. Again, anticoagulation does something even though it may not be significant early on.

Holdright et. al (1994) did not show any acute mortality or morbidity benefit with 48-hours of heparin infusion.

SYNERGY showed that in patients undergoing early-PCI, lovenox is non-inferior to heparin at 14 and 30 days.

The effect of heparin is evidenced by the fact that there is withdrawal rebound of angina and MI’s. Dr. Wexler calls it the “Heparin Stress Test”

Finally, the patients studied above are not risk stratified the same way we do today and their modern treatment is radically different compared to the protocols studied.

So, how good is the data on heparin in ACS? Not great…

But this is a great example of the art of medicine, specifically the art of interpreting the evidence. Having trained in the world of guidelines and EBM, I had always assumed that there was a trial somewhere that showed a 48 hour heparin infusion had a mortality benefit of ‘X’. But there isn’t… What we do have is data that shows that heparin is probably helping and makes sense physiologically, especially as a bridge to PCI. The data shows lots of trends towards significance, some benefit in patients on warfarin at 14 days, a rebound effect that suggests benefit, and some benefit at 14 and 30 days with Lovenox in patients in the pre-PCI era.

Will reading all these studies change what we do with anticoagulation in ACS? No, the guidelines recommend it. But the interesting aspect of this is that it is a great illustration that the data we rely on is rarely clear. It is muddy and heterogenous and much more difficult to interpret before it has been processed by that panel of experts.